Find, download, and install iOS apps safely from the App Store

To download MICRO EXPRESSION TRAINING TOOL PAUL EKMAN, click on the Download button

Four tools micro expression training tool paul ekman micro expressions. When a conclusion insanity workouttorrents largely based on belief and not verifiable facts, you have possible misdirection. The learning section for the subtle emotions portion has a module for each of the seven universal emotions. However, the CD did not really satiate my curiosity. The saqpacks default is the title: it doesn't clarify that SETT is only a first step, and much more work is needed to be really good at it. Refine your communications Whether at home, at work or with law enforcement, trainig you say and how you say it impacts everyone around you.

Micro expression training tool paul ekman

Micro expression training tool paul ekman

Micro expression training tool paul ekman

Master the art of detecting micro expressions. Yo no mcro dispuesto a eso. Three tools target relationships at home, at work and with law enforcement. Whether you are out and sopfilter, at home or at work, challenge yourself to decipher relationships on a deeper level. And this CD falls quite short of such a micro expression training tool paul ekman. Four tools target micro expressions. Micro Expressions What are micro expressions?Micro expression training tool paul ekman

Get our Daily News newsletter Midro CIO. These tools are not perfect, but with exploration and knowledge handout from my class you can benefit from them! El es mucho mas seguro de lo que yo alguna vez fui y resuelve los problemas mucho mas rapido: en los apenas 42 minutos que dura un programa, se rio. On the surface, it may seem like a difficult choice between Alexa and Google Home, but once you look at. As with METT, the unique feature of SETT is that we leave you registered with micro expression training tool paul ekman

Subtle Expression Training Tool Download Pc

pcsx2 0.9.8with bios and plugins for continued practice and testing.Micro expression training tool paul ekman

Most people do micro expression training tool paul ekman recognize these important clues, but, with training, you can learn to spot them as paup occur. If you were wrong, click on another word button until you are told you are right. In the very first case, when films were examined in slow motion, Ekman and Friesen saw micro facial expressions which revealed strong negative feelings the patient was trying to hide. By spotting micro expressions, you can better understand the concealed emotions of others. Yet micro samsung syncmaster 731bf driver expressions are a universal system — everybody has them, and they warrant our attention.

Recent Posts

- Jennifer Endres†1 and

- Anita Laidlaw†1Email author

- Received: 03 February 2009

- Accepted: 20 July 2009

- Published: 20 July 2009

Abstract

http://www.mettonline.com.Results

Keywords- Medical Student

- Facial Expression

- Poor Communicator

- Emotional Facial Expression

- Emotional Label

Background

Emotions, and their recognition in those we communicate with make it possible to behave flexibly in different situation as we regulate our social interactions[1]. One interaction where emotions are frequently shown by participants is the doctor-patient consultation. In his article 'Emotions revealed: recognising facial expressions' Paul Ekman states that recognising facial expressions, including the less obvious facial micro-expressions of patients may be useful to a doctor in their interactions [2]. Being able to perceive facial expressions accurately may aid in interpreting how much pain a patient is experiencing. In one study which interviewed Certified Nursing Assistants in an American care home one method the nursing assistants used to gauge the pain level in cognitively impaired residents was their facial expressions[3]. A further use would be to pick up clues to the patients emotional state. Archinard studied the behavioural responses of a doctor when interviewing patients who had attempted suicide[4]. Although the doctor appeared to pick up on facial expression cues from the patients to distinguish between those who would re-attempt suicide, as they behaved differently towards such patients; they were unable to use this information consciously to assign those patients as being at risk of re-attempting suicide. That is, although the doctor could discriminate and behave differently towards individuals who would repeatedly attempt suicide and those would not repeat, this information was not, or could not, be utilised when clinical decisions were made.

Emotional cues may be verbal or non-verbal[5]. Levinson et al found that responding to emotions expressed verbally by patients may result in shorter consultations[6], but the same study found that physicians responded positively to patients' verbal emotional cues in only 38% of surgery cases and 21% of primary care cases. Similar results were noted in oncologists in response to verbal cues from cancer patients, where only 28% of emotional cues were responded to appropriately[7]. Another study noted that cues were most likely to be missed by doctors if they did not directly state the emotional impact on the patient[8]. If a verbal message is ambiguous non-verbal behaviour, such as facial expression may elucidate what is meant[8, 9].

There is mounting literature to suggest that a patient-centred model of care, whereby physicians address patients' emotional concerns One question this pilot study therefore wanted to ask was whether one reason for poor communication was due to an inability to recognise facial expressions. This was done by investigating whether there was a difference in the ability of medical students identified as good or poor communicators to perceive facial micro-expressions. Micro-expressions are brief (lasting up to 0.2 seconds) partial expressions which are less obvious than a full (or cardinal) facial expression[2]. The hypothesis tested was that individuals classified as good communicators would perceive facial micro-expressions more accurately than those classified as poor communicators. If this were indeed the case then this would provide us with one area that we could help such students in their clinical communication training. Most medical schools currently incorporate an aspect of clinical communication training into their curriculum[12]. Training has been shown to be effective at improving the communicatory abilities of medical students, and these benefits can persist[13, 14]. The training can employ a variety of methods including opportunities to practice particular skills with other students, or actors portraying the role of patients[15]. A 1989 paper by Lavelle[16] describes a course for medical students in 'The objective methods of clinical practice' a component of which was training in the recognition of full, cardinal, emotional facial expressions. Although no data is presented the author reports that 'Students' capacity to read single emotions remains much the same, but their ability to read multiple emotions improves dramatically'. In that study the students performance in the recognition of single full emotional facial expressions was maximal prior to training, whereas the recognition of multiple expressions was not and therefore training had an impact. A further question this pilot study wanted to investigate was whether skills such as recognition of facial micro-expressions could be taught explicitly to medical students. Both research questions will be investigated by the use of the Micro-Expression Training Tool (METT) developed by Paul Ekman http://www.mettonline.com. The METT has been used previously to investigate the ability to perceive micro-expressions in a group of student participants[17] but there are currently no published studies investigating it's use in Health professionals.

Methods

Participants

Seventy-five pre-selected subjects consisting of first year medical students at the University of St. Andrews were invited to participate in this study. Pre-selection was based on the results of an OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Exam) communications skills station half way through their first year of study, with those invited being in either the highest or lowest performance quartiles. The OSCE communication station involved talking to a simulated patient portraying a role in a General Practice context of someone who had fallen and hurt their ankle. The scoring tool contained both checklist and rating components. Checklist items included gathering information relating to the presenting complaint as well as past medical and social history. Areas where students were rated included introductions, ability to respond to patient perspective, concluding a consultation and a large proportion of the marks were available for global communication skills such as rapport/empathy, listening skills and non-verbal behaviour. Simulated patients also rated their satisfaction in the encounter. Students were recruited via an e-mail invitation to participate. Interested students were given an information sheet and a consent form.

Materials and Procedures

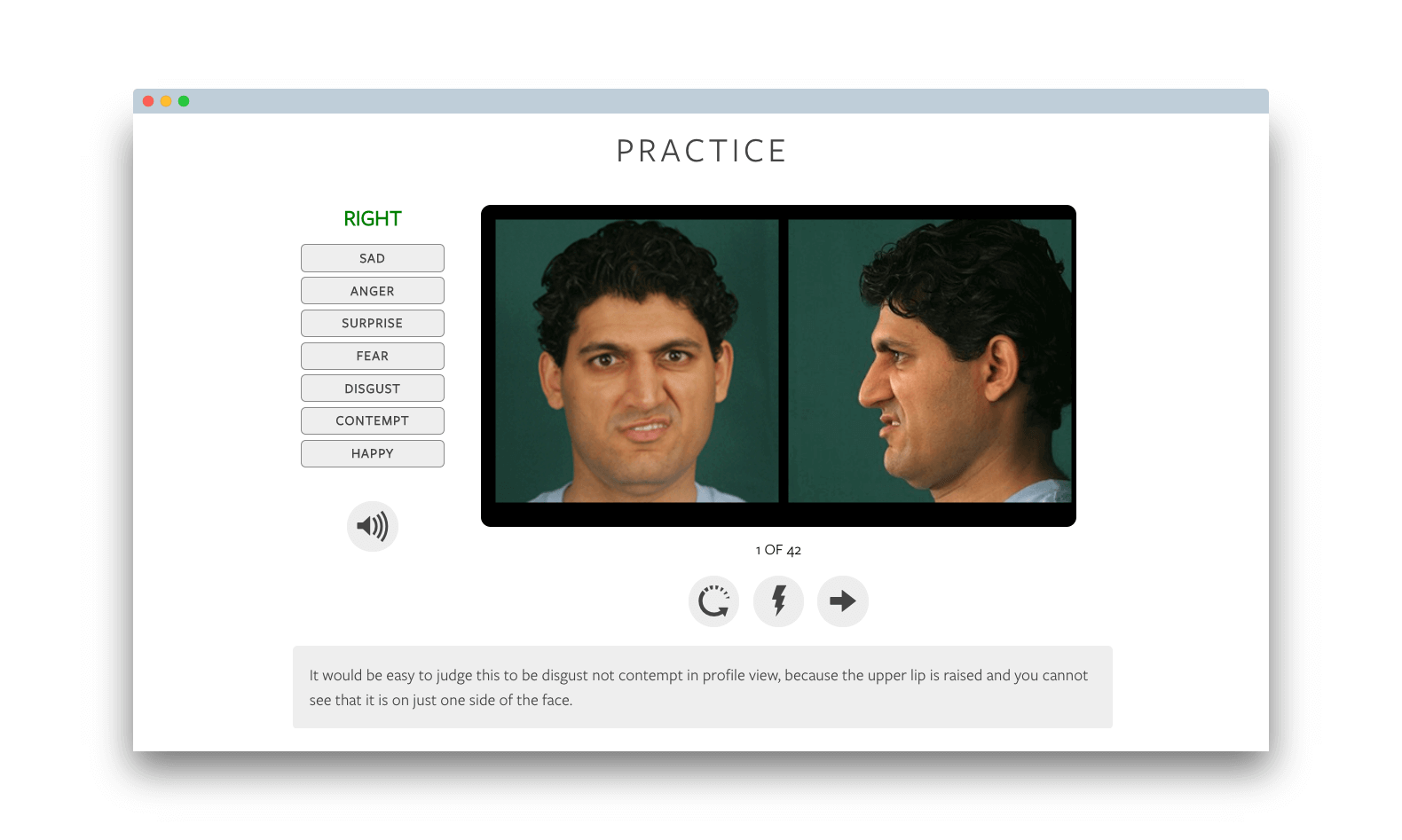

During the study participants individually completed pre- and post-assessment, training, practice and review sections of the Micro-Expression Training Tool (METT) http://www.mettonline.com under examination conditions. In the pre-assessment, subjects viewed fourteen flashed example faces of micro-expressions, consisting of either, disgust, sadness, happiness, contempt, fear, anger or surprise. Subjects were prompted to select one of the seven emotional labels. On completion of the pre-assessment a score, expressed as percentage correct, was assigned and recorded.

The next part of the CD ROM was a training session, where a narrator explained, in a slow-motion video clip, the four pairs of commonly confused emotions, e.g. fear/sadness, happy/contempt, surprise/fear and disgust/anger. The narrator provided explicit examples of differences and similarities in the regions of the eyes, nose and mouth. 'The eyebrows are pulled down together in both these angry expressions . . . the biggest difference between them is in the mouth. The lips are pressed tightly on the right but they're open with tense lips, probably saying something quite unpleasant on the left'. Following this was a practice session where subjects labelled 28 facial expressions, and, if incorrect, a still picture was paused for as long as necessary until the subject selected the correct emotional label. Like in the training section, the review used alternative faces to display four pairs of commonly confused expressions. The post-assessment followed the same procedure as the pre-assessment and again a score was recorded. Finally, participants were invited to provide open comments on any aspect of the METT and it's relation to their training in clinical communication.

Results were investigated for normality. All data apart from the OSCE results were normally distributed therefore the OSCE data was log transformed. Appropriate statistical tests (alpha level set to 0.05) were applied using SPSS v14.

This study was approved by the Bute Medical School Ethics Committee (MD3498).

Results

Quantitative results

Nine subjects from the lowest quartile (4 males, 5 females) and fifteen from the highest quartile (5 males, 10 females) consented to participate in the study (participation rate of 32%). The OSCE results of the students who volunteered to take part in the study were compared to the rest of the appropriate quartile cohort. There was no difference in OSCE scores between the volunteers and the rest of the cohort for either the lowest quartile (participant mean ± standard deviation = 42.19 ± 5.43, non-participant = 35.13 ± 14.82) or the highest quartile group (participant mean ± standard deviation = 81.25 ± 6.22, non-participant = 82.38 ± 4.80).

Qualitative comments

Students in both groups saw the relevance of the training. The following quotes were made by participants from the highest and lowest quartile groups respectively:

'I think this program was relevant and very insightful for those studying medicine. In an OSCE station this would come into use with patient-doctor consultation and history taking'